Warning: This article discusses Dawn of the Planet of the Apes in depth, so don't read until you've seen the film.

Pierre Boulle wrote the novel Planet of the Apes in 1963. He created an absurd and ingenious vision of a planet where civilization had been turned upside

down. On this alien planet apes- who drove cars and wore suits- ruled over

primitive humans. The novel had depth but when it was adapted in to the classic

1968 film with Charlton Heston the story became a much darker allegory. In the novel the ape planet was an alien world light years from Earth. The film’s

ending reveals that Heston’s astronaut George Taylor was on Earth along. He

discovers the ruins of the statue of liberty on the shore. This image of the statue symbolizes mankind’s

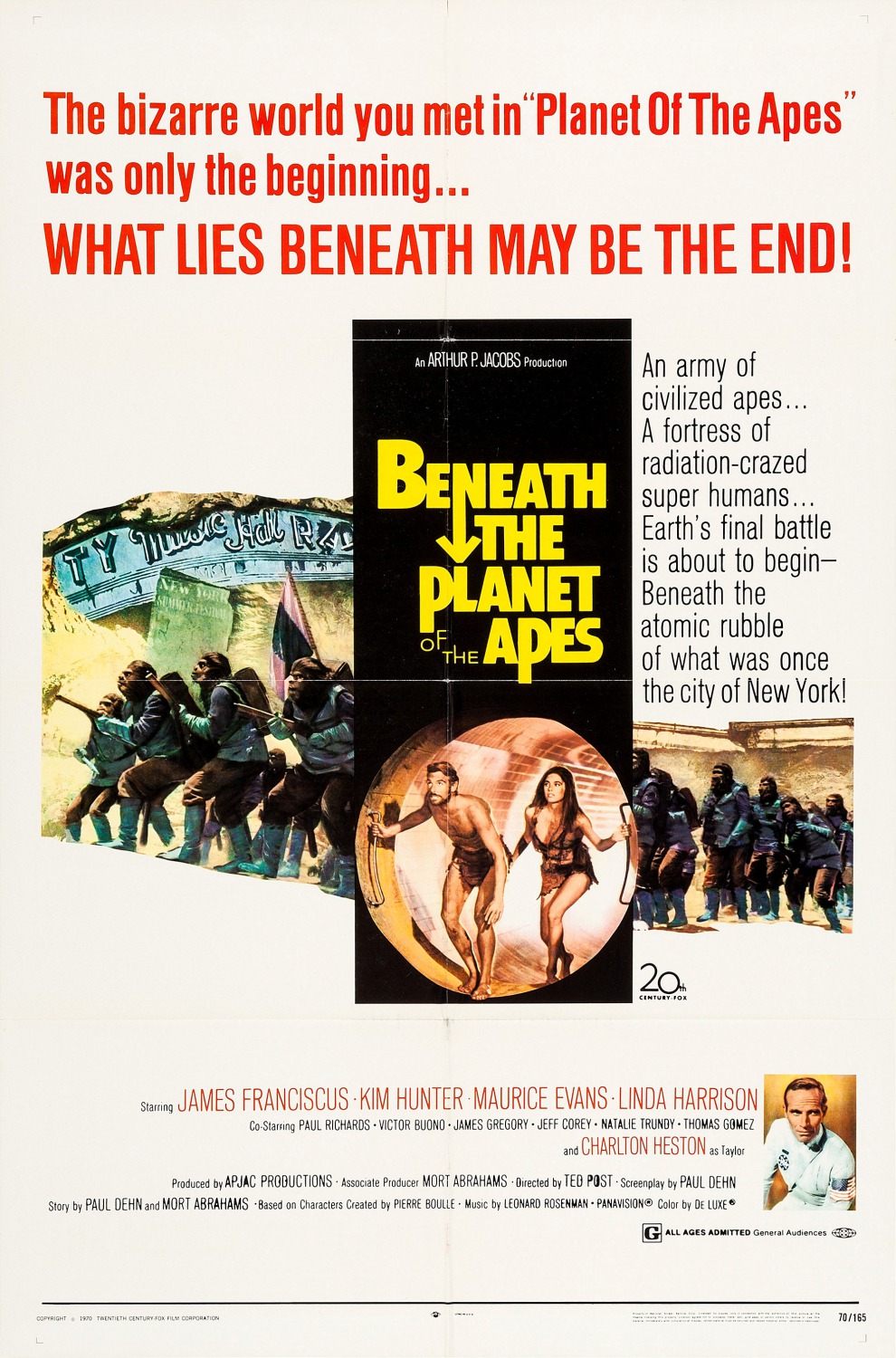

ultimate self-destruction. As the series progressed through four sequels the

films became even bleaker and we found ourselves becoming emotionally invested

in the ape characters. The mythology also deepened and expanded, eventually becoming a circular tale via time travel.

In 2011’s Rise of the Planet of the Apes and this year's Dawn of the Planet of the Apes we're no longer merely in the realm of the absurd. Instead we’re treated with a world that

feels remarkably real and emotionally immediate. These films lean toward a more

realistic take on the mythology, which isn’t too surprising given Hollywood’s

tendency to “ground” certain genre properties nowadays. But thankfully these two films

aren’t self-consciously grim and gritty. Even so, the Planet of the Apes series was never without its dark elements.

Moreover- these two films are so distanced in the timeline from the world of

the original film- that this tonal grounding doesn’t feel like posturing on

behalf of the filmmakers.

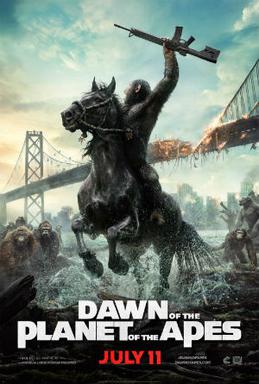

Dawn of the Planet of

the Apes does the mythology justice and succeeds as both a standalone film

and a sequel to Rise of the Planet of the

Apes. Dawn builds upon the

foundation laid in its predecessor, both enriching the first film as well as

using that foundation to tell a complex story about the quest for peace and the

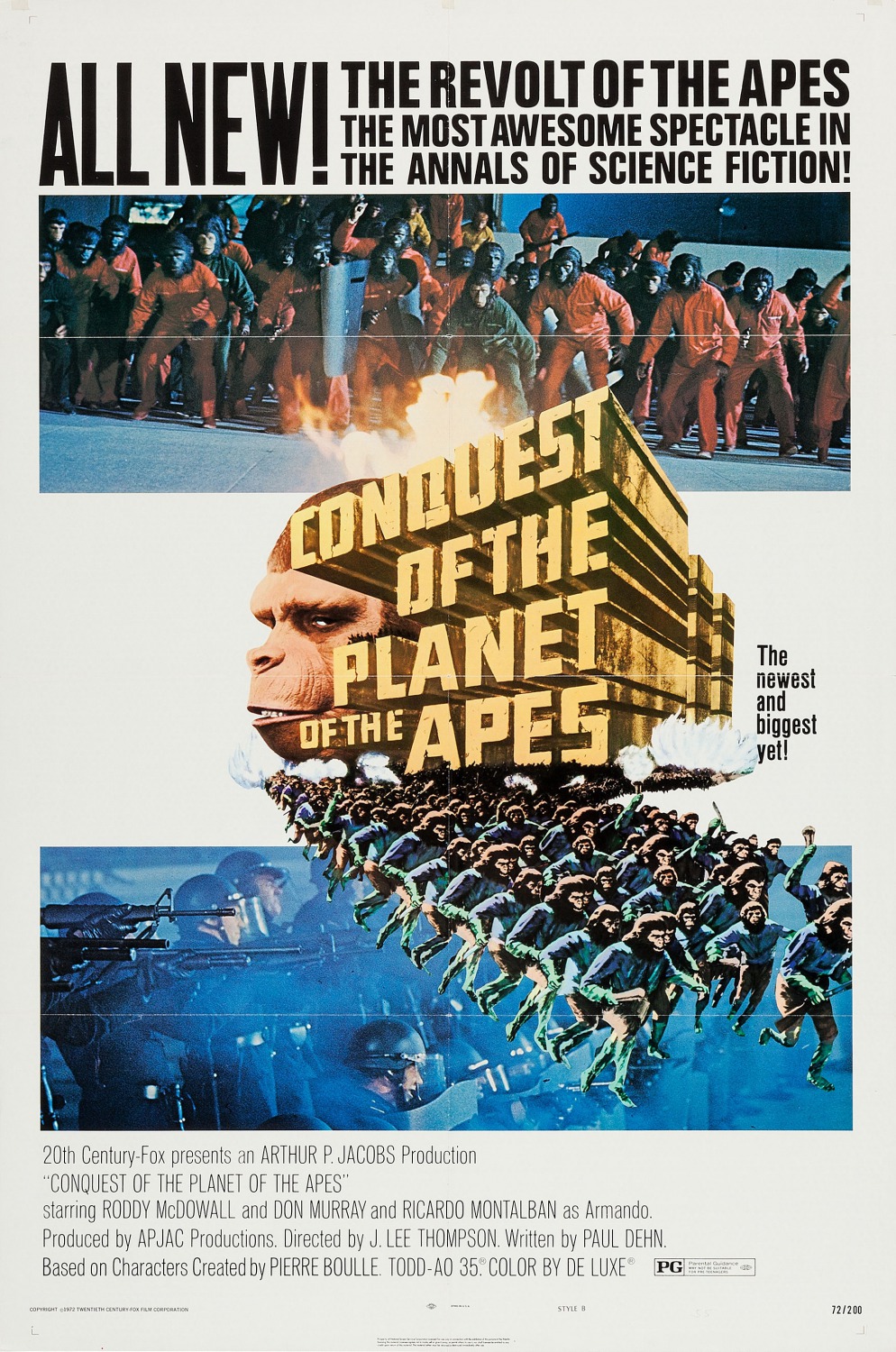

possibility of co-habitation between apes and humans. Rise was a re-working of

the series fourth installment, Conquest of

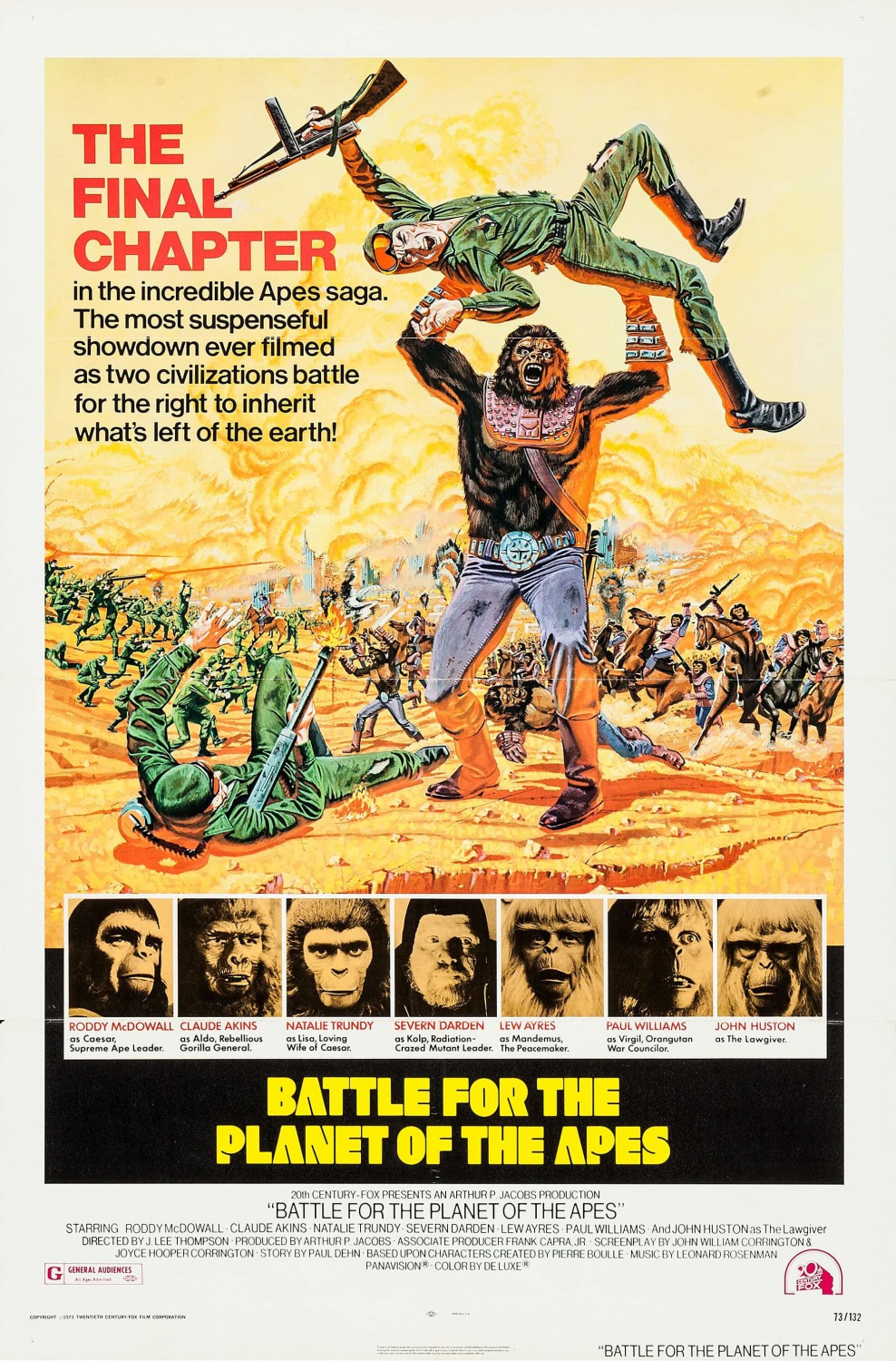

the Planet of the Apes. Dawn, in

turn, reinterprets the final film in the series, Battle for the Planet of the Apes. On paper, using the fourth and

fifth films in a franchise as the basis for a new starting point for a series seems

odd. But in the case of Planet of the Apes,

these films make sense in terms of re-starting the franchise. Taking influence

from Conquest and Battle allows the new series to work

both as a spiritual prequel to the original film as well as doing something

different with this franchise rather than just re-visiting the initial concept.

Dawn takes place

10 years after the events of Rise. After

the obligatory news broadcast opening, which details the spread of the simian

flu- the result of scientific testing on apes in the pursuit of finding a cure

for Alzheimer’s- we’re reintroduced to Caesar (played via motion capture by

Andy Serkis)-the hyper intelligent ape around which the first film largely

centred. Caesar now rules over a clan of apes in post-apocalyptic Earth. I do love the opening scenes of the apes hunting food- which harkens back to apes hunting humans in the original film- then returning to their home, where we see them living a peaceful existence, no longer in fear of captivity. The apes are unsure that humanity even still exists but are soon made aware of human survivors.

They come in to the apes' forest, hoping to

gain access to a dam that could provide power to the city in which

many remaining humans live. The apes tell them to go away, which shocks the humans, since they didn't know the apes were capable of speech. Caesar and the apes

follow the humans back to the city. Caesar states that apes don’t want war.

He wishes for the humans to stay in their territory while the apes will stay in

theirs. Malcolm (Jason Clarke) goes back to the forest in an attempt to persuade

Caesar to allow them access to the dam. Caesar concedes but his second in command Koba

(Toby Kebbell) presents a threat; he still harbours hatred toward humans from

his days being a guinea pig.

Caesar isn’t entirely a pacifist but he’s no war-monger

either. He doesn’t want to go to war with humans, though Koba does. Caesar

feels that by allowing the humans access to the dam he’s working in the best

interests of his kind, avoiding any conflict that could get the apes killed. But

it’s evident that Caesar has learned kindness and compassion from the noble

humans he’s met. He also sees Malcolm is a good man and senses the humans are

desperate.

Caesar and Koba represent “two sides of the same coin.” Both

were the result of testing by humans that made being super intelligent- and both

were imprisoned by humans and treated with cruelty. But while Caesar knew love

from his surrogate father, scientist Will Rodman (James Franco) and Will's Alzheimer’s

stricken father Charles (John Lithgow), Koba never knew love from humans. When

Caesar mentions that humans need to work on the dam Koba points to his

numerous scars and repeats “Human. Work.” It’s this moment that encapsulates Koba’s

back-story and his view on humanity. Caesar doesn’t completely trust humans but

he’s left a lot of his bitterness behind, becoming a family man- married to

Cornelia (a underused Judy Greer) and the father to both Blue Eyes (Nick Thurston)

and a new born ape. Koba is a complete lone wolf (or ape).

There’s almost something Shakespearean about the power play

between Caesar and Koba. Like many characters in Shakespeare, including the

kings, Caesar is brought down by someone he trusted. Akin to his namesake,

Caesar has a Brutus, which is Koba. There’s even a silent “Et tu Brute?”

between them. Koba shoots Caesar using a human gun and blames the supposed

assassination on the humans, leading the apes in battle against the humans. Caesar

“loved wisely but not well," to quote Othello. He tells Blue Eyes- after Koba has taken over the city- that he trusted Koba because he

was an ape.

Caesar’s character arc through this film leads to the

realization that apes can be as treacherous as humans. When Malcolm finds Caesar

alive, Caesar has them stop at his former house. He views the video recording

of Will teaching him sign language. Caesar and the audience are reminded in

this scene of how far Caesar has come, from a baby to a revolutionary to a leader. I also

think this video shows Caesar how the love he received from Will is what made him trust Malcolm. When Malcolm asks who was on the video

Caesar simply tells him “A good man. Like you.” Malcolm and Caesar don’t have

the same emotional connection as Will and Caesar but a mutual respect grows

between them.

One element I found fascinating while thinking back on the

film relates to its anti-gun message. While it’s Koba’s actions that lead to

the mass violence in the story the film uses the image of a gun to represent the threat between ape and human peace.Caesar doesn’t want the humans to bring in guns. In

one scene it’s discovered that Carver (Kirk Acevedo) has brought in a gun. This

leads to tension after a charming moment between Ellie (Keri Russell) and

Caesar and Cornelia’s baby. Koba uses a gun to frame the humans for Caesar’s

death and manipulate the apes in to violence.

The anti-gun message stands out to me because Charlton

Heston- the star of the original film- became infamous for being the president

of the NRA in his late years. He famously declared “From my cold dead hands” in

defense of the second amendment. While I won’t be as presumptuous as to say the

film is an attack on Heston’s political views, it’s hard to imagine that the image Heston created for himself wasn’t in the back of the screenwriters’ minds. The

issue of gun rights has arguably never been a more pressing issue in the States

then it is now. The Apes films always

commented on the state of the world during the 60s/70s. It only seems

appropriate that the film would confront this particular issue.

While most blockbusters present violence and destruction as

the only means to defeat evil, violence doesn’t solve anything in this film.

Even when Koba is defeated his actions have led humans and apes to brink of

war. Despite having some spectacular images of apes on horsebacks using machine

guns (which to be fair is awesome) and a stunning action climax, Dawn is sincerely anti-violence. As in Battle the

apes themselves even preach against violence against their own kind. main ape commandment is “ape shall never kill ape.” To be better than humans the apes must not murder each other like humans. Koba breaks this commandment

when he kills Rocket’s son Ash, who won’t kill a human. Despite hating humans,

Koba is not above killing apes if they stand in the way of destroying

humanity. By killing an ape Koba shows that he's no better then the humans he despises. He's capable of the same treachery and murder of his own kind.

And as a

leader, Koba is the opposite of Caesar, a tyrant.

Koba hangs on a edge

at the film’s climax, after a fight between him and Caesar. He says to

Caesar “Ape shall never kill ape,” to which Caesar grabs his hand and

then intones “You are not ape,” letting him fall, echoing Koba’s execution of

Steven Jacobs (David Oyelowo) at the end of Rise. By betraying the commandment Koba is no

longer an ape. He’s a twisted version of an ape that needs to be let go. But

while Koba dies he still gets what he wants, a war between apes and humans. The ending of the film is similar to that of

Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight in that the heroes don’t really win. Caesar

didn’t want a war but now he has to fight against humans if his kind is to

survive. Just as how Batman had to take the fall for Harvey Dent’s crimes to

save Gotham's soul.

Malcolm tells Caesar he thought humans and apes had a chance

to live peacefully together. Caesar replies that he did too, calling Malcolm

his friend. This is an incredibly sad ending. Malcolm and Caesar parting ways represents the final breaking of apes and humans, the destroyed hope of peaceful co-habitation

Similar to Rise, Dawn’s main flaw is the characterization regarding its human characters is a touch too thin. I really wish I got to know these people a little better. I do, however, like that the film allows these people to share very human moments. The characters as a result aren’t completely soulless. I like the parallel between Malcolm and Caesar being fathers who are attempting to get close to their sons. Malcolm’s son Alexander (Kodi Smit-McPhee) is still adjusting to his new step mom, the aforementioned Ellie. The film is very male dominated. The female characters- Ellie and Cornelia- have even less characterization than the males. Clarke makes a solid lead, showing both vulnerability and an inner strength. Russell does well with what little she’s given. Gary Oldman also does fine work as Dreyfus, the human leader. While Dreyfus could’ve been made in to a shallow human villain there’s an devastating moment where we learn what Dreyfus has lost.

Matt Reeves takes over the director’s chair from Rise’s Rupert Wyatt. This is Reeves’ fourth film, following The Pallbearer, (1996) Cloverfield (2008) and Let Me In (2010), the remake of the Swedish Vampire film Let The Right One In (2008). Reeves is also known as the creator of the TV series Felicity (starring Russell.) Let Me In is the only previous directorial effort from Reeves that I had seen before this film. While that film strewed too close to the original, Reeves’ direction was elegant and his command of tone impressive. Reeves bring that same directorial elegance to this film. While there is plenty of action as the film progresses, Reeves doesn’t stage the action in an empty, bombastic fashion. The ape attack on the city has real dramatic weight and a conscious sense of horror to it. A 360 degree shot on the top of a tank blends beauty and utter destruction majestically. This shot reminds me of the shot from Let Me In, in which we're in a car as it rolls over. Like Wyatt, Reeves favours build up to outright bombast. This is even more leisurely paced in some ways than Rise was. But I like how the film is more interested in story-telling and atmosphere then it is in set pieces.

The motion capture work in the previous film was impressive but it feels like it’s on another level here. Serkis has revolutionized film acting over the last decade. His work as Gollum changed how we thought about CGI characters on film. His work on Caesar is even more nuanced and emotional. To me Caesar feels as real any modern film character and it’s been amazing witnessing his journey as a character over these two films. Kebbell also deserves props for making Koba a haunted antagonist, a character whose evil masks their own hatred and bitterness. Koba is an incredibly tragic character who’s as important to this film as Caesar.

I don’t want to oversell Dawn of the Planet of the Apes but I think Hollywood would be in better shape if more blockbuster type films were like this. In its strongest moments it comes as close to an artistic vision we’ve seen in a franchise tent pole this summer. Rise and Dawn show that franchise films don’t have to be completely corporate mandated and soulless- that there’s potential to create compelling stories using a familiar brand. Both RIse and Dawn have redefined- for me at least- how I view this franchise and what it’s capable of artistically. And I'm excited to see where the series goes next.